Defining "domestic violence" in your workplace violence policy & program

In this post, I explore the origins of Ontario's domestic violence provision under the Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA) and how to interpret the term “domestic violence” in the absence of a statutory definition. Drawing on government guidance, legislation from other jurisdictions, and leading expertise in family violence, I argue that workplace violence policies must offer a comprehensive understanding of domestic violence. Without this, employers cannot meet their legal duty to protect workers under OHSA.

The legislative context

Over 15 years ago, OHSA was amended to include a requirement that employers take reasonable precautions to protect workers from domestic violence at work:

Domestic violence

32.0.4 If an employer becomes aware, or ought reasonably to be aware, that domestic violence that would likely expose a worker to physical injury may occur in the workplace, the employer shall take every precaution reasonable in the circumstances for the protection of the worker.

This amendment was passed in response to the workplace murder of Lori Dupont by her former partner. Yet, many workplace violence policies I review omit any mention of domestic violence or merely quote the provision without training or context. That omission renders the law ineffective.

If we want section 32.0.4 to have meaning, we must start with a clear understanding of what domestic violence actually is.

Section 32.0.4 was a response to the murder of Lori Dupont by her former partner at work. You can see ONA's video on the subject here.

Where to turn when there's no statutory definition

Ontario law does not define “domestic violence” under OHSA. But this doesn’t mean employers can ignore it. In fact, a proper understanding of the term is necessary to:

- identify when non-physical forms of violence may escalate into physical forms of violence (s. 32.0.4);

- identify when domestic violence may show up at the workplace (s. 32.0.4);

- determine what a “reasonable” precaution would be in response to an identified risk (s. 32.0.4);

- determine how to implement those reasonable precautions (s. 32.0.4);

- teach its workers how to identify, mitigate, and respond to risks of physical domestic violence at work (para. 25(2)(a) and s. 32.0.4); and

- “take every precaution reasonable in the circumstances for the protection of a worker” (s. 25(2)(h)).

Choosing ignorance only risks violating OHSA (and attracting related penalties, including fines and even imprisonment).

What guidance is available

To define domestic violence, we can draw on three key sources:

- Interpretive guidance from the government

Ontario's Employment Standards Act Policy and Interpretation Manual offers helpful guidance:

[A]s a guideline, domestic violence may include physical, emotional or psychological abuse or an act of coercion, stalking, harassment or financial control. A threat of such abuse is also covered by this provision. It may be committed by an employee’s current or former spouse or intimate partner, or between an individual and a child who resides with the individual or between an individual and an adult or child who is related to the individual by blood, marriage, foster care or adoption. [emphasis added]

This definition highlights the role of power and control, and crucially, it acknowledges non-physical abuse.

- Statutory definitions elsewhere in Canada

Across Canada, statutes define domestic violence using broad and inclusive language. Common elements include:

- Psychological abuse, including coercive control

- Damage to property, including pets

- Forced confinement

- Deprivation of basic necessities

- Stalking and harassment

- Financial abuse

- Witnessing abuse

- Human trafficking

Relevant laws include:

- the federal Divorce Act, s. 2(1) (“family violence”);

- Yukon's Employment Standards Act, s. 60.03.01(2) (“domestic violence”);

- the Northwest Territories' Protection Against Family Violence Act, s. 1(2) (“family violence”) (incorporated by reference in the Employment Standards Act);

- Nunavut's Family Abuse Intervention Act, s. 3(1) (“family abuse”) (incorporated by reference in the Labour Standards Act but not yet in force);

- BC's Employment Standards Act, s. 52.5(1) (“domestic or sexual violence”);

- Alberta's Employment Standards Code, s. 53.981(2) (“domestic violence”);

- Saskatchewan's The Victims of Interpersonal Violence Act, s. 2(e.1) (“interpersonal violence”) (incorporated by reference into The Saskatchewan Employment Act);

- Manitoba's The Domestic Violence and Stalking Act, s. 59.11 (“interpersonal violence”) (incorporated by reference into The Employment Standards Code);

- Nova Scotia's Labour Standards Code, s. 60Y (“domestic violence”);

- PEI's definition of domestic violence, paras 1(1)(a) and (c) of the Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence Leave Regulations under the Employment Standards Act (“domestic violence” and “intimate partner violence”);

- Newfoundland's Family Violence Protection Act, s. 3(1) (“family violence”) (incorporated by reference into the Labour Standards Act); and

- Bill C-332 has also passed, which will introduce a definition for coercive control in s. 264.01 of the Criminal Code.

- Family violence experts

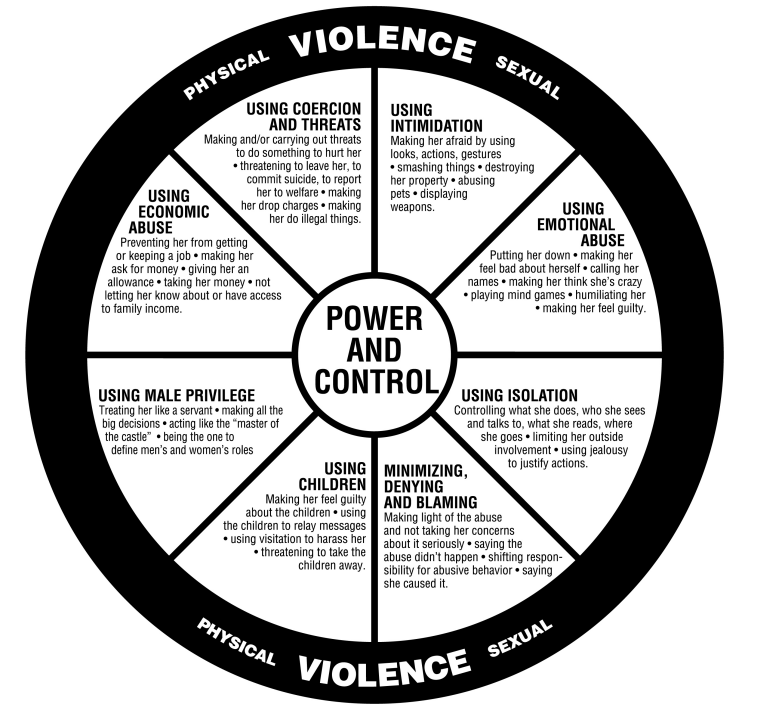

Created by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs (“DAIP”) in the 1980s, the Power and Control Wheel (the “Wheel”) is used globally to illustrate patterns of abuse. It depicts how non-physical violence often persists between (or instead of) episodes of physical abuse. These tactics can include:

- Isolation

- Economic control

- Gaslighting

- Intimidation

- Threats of further harm

Copyright: Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs

Understanding domestic violence as a pattern of coercive control is critical. The Wheel shows that even when the physical violence stops, the abuse often continues in other, more insidious forms.

Why this matters

Under s. 32.0.4, employers must take every reasonable precaution if domestic violence likely to cause physical injury may occur in the workplace. But that requires:

- Recognising non-physical abuse as a potential red flag

- Understanding intersectional risk factors (e.g. race, disability, immigration status)

- Building this knowledge into policies and training

Domestic violence is often gendered and ongoing. Without proper training and a full understanding of the issue, employers cannot meet their legal obligations.

Next steps for employers

To meet the requirements of OHSA s. 32.0.4, employers should:

- Include a comprehensive definition of domestic violence in their workplace violence policy. Consider:

- Requesting permission to use the Power and Control Wheel from DAIP

- Referencing broad legislative definitions (e.g. Divorce Act, BC's ESA, Bill C-332)

- Using the policy builder at dvatwork.ca by Western University

- Train your team. Policy without training is ineffective. Training must cover:

- How to recognise signs of domestic violence

- How to respond appropriately

- How to assess and implement reasonable precautions

dvatwork.ca provides a helpful policy builder for employers

Conclusion

Domestic violence is not limited to physical harm. It is often persistent, coercive, and invisible to the untrained eye. For §32.0.4 to have real impact, workplace violence policies must name and explain domestic violence in full.

In an upcoming post, I’ll explore best practices for training your team to recognise and respond to domestic violence at work.

- The Wheel uses "she/her/hers" pronouns for the survivor and "he/him/his" pronouns for the abuser to reflect the gendered nature of domestic violence. This does not mean that all abusers are men and all survivors are women. Domestic violence can affect anyone in all types of intimate partner relationships.

- Bearing in mind the intersectional nature of domestic violence, DAIP also offers wheels that have been adapted to the unique circumstances of certain BIPOC, 2SLGBTQIA+, immigrant, and ethnoreligious communities. For example:

- invoking the Bible to justify the abuse or threatening divorce where prohibited by the survivor's faith;

- using dating apps (e.g. Grindr) to interrogate people the survivor is chatting or hooking up with; and

- threatening to report the survivor to Immigration.

- * This policy builder assumes a federally-regulated employer. You will need your lawyer to help transform some of the provisions to apply in Ontario (or whatever other jurisdiction you may belong to).

.png)

.png)